Howard Thurman

Howard Thurman | |

|---|---|

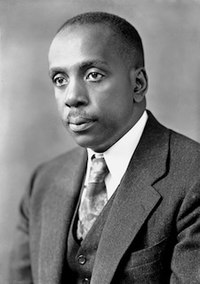

Thurman at Howard University (1932–1944) | |

| Born | Howard Washington Thurman November 18, 1899 Daytona Beach, Florida, United States |

| Died | April 10, 1981 (aged 81) San Francisco, California, United States |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation(s) | Minister, theologian, author, dean |

| Organization(s) | Howard University Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples Boston University |

| Notable work | Jesus and the Disinherited (1949) |

Howard Washington Thurman (November 18, 1899 – April 10, 1981) was an American author, philosopher, theologian, Christian mystic, educator, and civil rights leader.

As a prominent religious figure, he played a leading role in many social justice movements and organizations of the twentieth century.[1] Thurman's theology of radical nonviolence influenced and shaped a generation of civil rights activists, and he was a key mentor to leaders within the civil rights movement, including Martin Luther King Jr.

Thurman served as dean of Rankin Chapel at Howard University from 1932 to 1944 and as dean of Marsh Chapel at Boston University from 1953 to 1965. In 1944, he co-founded, along with Alfred Fisk, the first major interracial, interdenominational church in the United States.[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Howard Thurman was born in 1899 in Florida in Daytona Beach. He spent most of his childhood in Daytona, Florida, where his family lived in Waycross, one of Daytona's three all-black communities.[3]: xxxi, xxxvii, xci

He was profoundly influenced by his maternal grandmother, Nancy Ambrose, who had been enslaved on a plantation in Madison County, Florida. Nancy Ambrose and Thurman's mother, Alice, were members of Mount Bethel Baptist Church in Waycross and were women of deep Christian faith.

Thurman's father, Saul Thurman, died of pneumonia when Howard Thurman was seven years old. After completing eighth grade, Thurman attended the Florida Baptist Academy in Jacksonville, Florida. One hundred miles from Daytona, it was one of only three high schools for African Americans in Florida at the time.[3]: xxxi–xli

In 1923, Thurman graduated from Morehouse College as valedictorian.[3]: xciv In 1925, he was ordained as a Baptist minister at First Baptist Church of Roanoke, Virginia, while still a student at Rochester Theological Seminary (now Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School).[3]: xcvi He graduated from Rochester Theological Seminary in May 1926 as valedictorian.[3]: lxi, xcvii

From June 1926 until the fall of 1928, Thurman served as pastor of Mount Zion Baptist Church in Oberlin, Ohio.[3]: xcvii, c In the fall of 1928, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where he had a joint appointment to Morehouse College and Spelman College in philosophy and religion.[3]: c During the spring semester of 1929, Thurman pursued further study as a special student at Haverford College with Rufus Jones, a noted Quaker philosopher and mystic.[3]: ci He enjoyed praying and going to church which provided him part of his education.

Marriage and family

[edit]Thurman married Katie Kelley on June 11, 1926, less than a month after graduating from seminary. Katie was a 1918 graduate of the Teacher's Course at Spelman Seminary (renamed Spelman College in 1924). Their daughter Olive was born in October 1927. Katie died in December 1930 of tuberculosis, which she had probably contracted during her anti-tuberculosis work. On June 12, 1932, Thurman married Sue Bailey, whom he had met while at Morehouse, when Sue was a student at Spelman.[3]: lxii–lxiii, lxvii, lxix–lxxii Their daughter Anne was born in October 1933. Sue Bailey Thurman was an author, lecturer, historian, civil rights activist, and founder of the Aframerican Women's Journal. She died in 1996.

Career

[edit]

Thurman was selected as the first dean of Rankin Chapel[4] at Howard University in the District of Columbia in 1932. He served there from 1932 to 1944. He also served on the faculty of the Howard University School of Divinity.[5]

Thurman traveled broadly, heading Christian missions and meeting with world figures.[6] In 1935-36 he led a six-month delegation of African-Americans invited to India for meetings. At Bardoli they spoke with Mahatma Gandhi, who asked "persistent, pragmatic questions" about the Black American community and its struggles. Training for satyagraha was discussed, its difficulties in the extreme addressed.

When Thurman asked Gandhi what message he should take back to the United States, Gandhi said he regretted not having made nonviolence more visible as a practice worldwide and remarked "It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world".[7][8]

In 1944, Thurman left his tenured position at Howard to help the Fellowship of Reconciliation establish the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples also known as The Fellowship Church in San Francisco. He served as co-pastor with a white minister, Alfred Fisk. Many of their congregants were African Americans who had migrated to San Francisco from Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas for jobs in the defense industry. The church helped create a new community for many in San Francisco.

Thurman was invited to Boston University in 1953, where he became the dean of Marsh Chapel (1953–1965). He was the first black dean of a chapel at a majority-white university or college in the United States. In addition, he served on the faculty of Boston University School of Theology. Thurman was also active and well known in the Boston community, where he influenced many leaders. Thurman was the minister delivering the sermon at Marsh Chapel on Good Friday April 20, 1962; the famous Good Friday double-blind psychedelic experiment by Walter Pahnke using psilocybin to assess whether a religious environment influenced a mystical experience.

After leaving Boston University in 1965, Thurman continued his ministry as chairman of the board and director of the Howard Thurman Educational Trust in San Francisco. He reportedly received a Doctor of Divinity degree from BU in 1967.[9][10]

Thurman was a prolific author, writing twenty books on theology, religion, and philosophy. The most famous of his works, Jesus and the Disinherited (1949), deeply influenced Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders, both black and white, of the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Thurman had been a classmate and friend of King's father at Morehouse. King visited Thurman while he attended BU, and Thurman in turn mentored his former classmate's son and his friends. He served as spiritual advisor to King, Sherwood Eddy, James Farmer, A. J. Muste, and Pauli Murray.

At BU, Thurman also taught Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, who cited Thurman as among the teachers who first compelled him to explore mystical trends beyond Judaism.[11]

Death

[edit]Howard Thurman died due to a lingering illness on April 10, 1981, in San Francisco, California. He was 81 years old.[12]

Honors and legacy

[edit]

In 1935, Thurman received an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, Morehouse.[13] Ebony Magazine at one point called Thurman one of the 50 most important figures in African-American history. In 1953, Life rated Thurman among the twelve most important religious leaders in the United States. Thurman was named honorary Canon of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York City, in 1974.[14]

In 1986, Dean Emeritus George K. Makechnie founded the Howard Thurman Center at Boston University to preserve and share the legacy of Howard Thurman.[15] In 2020, the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground moved to a larger space occupying two floors in the Peter Fuller Building at 808 Commonwealth Avenue.[16] The Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University holds the Howard Thurman Papers and the Sue Bailey Thurman Papers, where they are catalogued and available to researchers.[17]

The Howard Thurman Papers Project was founded in 1992. The Project's mission is to preserve and promote Thurman's vast documentary record, which spans 63 years and consists of approximately 58,000 items of correspondence, sermons, unpublished writings, and speeches. The Howard Thurman Papers Project is located at Boston University School of Theology.[18]

Howard University School of Divinity named their chapel the Thurman Chapel in memory of Howard Thurman.[19]

Howard Thurman's poem 'I Will Light Candles This Christmas' has been set to music by British composer and songwriter Adrian Payne, both as a song and as a choral (SATB) piece. The choral version was first performed by Epsom Choral Society in December 2007. An arrangement for school choirs, which can be performed in one or two parts with piano accompaniment, was first performed in December 2010.[citation needed][importance?]

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- The Greatest of These (1944)

- Deep River: Reflections on the Religious Insight of Certain of the Negro Spirituals (1945) [also published as The Negro Spiritual Speaks of Life and Death (same year)]

- Meditation for Apostles of Sensitiveness (1948)

- Jesus and the Disinherited (1949)

- Deep is the Hunger: Meditations for Apostles of Sensitiveness (1951)

- Christmas Is the Season of Affirmation (1951)

- Meditations of the Heart (1953)

- The Creative Encounter: An Interpretation of Religion and the Social Witness (1954)

- The Growing Edge (1956)

- Footprints of a Dream: The Story of the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples (1959)

- Mysticism and the Experience of Love (1961)

- The Inward Journey: Meditations on the Spiritual Quest (1961)

- Temptations of Jesus: Five Sermons Given By Dean Howard Thurman in Marsh Chapel, Boston University, 1962 (1962)

- Disciplines of the Spirit (1963)

- The Luminous Darkness: A Personal Interpretation of the Anatomy of Segregation and the Ground of Hope (1965)

- The Centering Moment (1969)

- The Search for Common Ground (1971)

- The Mood of Christmas (1973)

- A Track to the Water's Edge: The Olive Schreiner Reader (1973)

- The First Footprints (1975)

- With Head and Heart: The Autobiography of Howard Thurman (1979)

- For the Inward Journey: The Writings of Howard Thurman (1984) (selected by Anne Spencer Thurman)

Edited collections

[edit]- Fluker, Walter Earl; et al., eds. The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Vol. 1: My People Need Me, June 1918-March 1936. Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2009.

- Fluker, Walter Earl; et al., eds. The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Vol. 2: Christian, Who Calls Me Christian? April 1936-August 1943. Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2012.

- Fluker, Walter Earl; Eisenstadt, Peter; and Glick, Silvia P., eds. The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Vol. 3: The Bold Adventure, September 1943-May 1949. Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2015.

- Fluker, Walter Earl; et al., eds. The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Vol. 4: The Soundless Passion of a Single Mind, June 1949-December 1962. Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2017.

- Fluker, Walter Earl; et al., eds. The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Vol. 5: The Wider Ministry, January 1963–April 1981. Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2019.

- Fluker, Walter Earl and Tumber, Catherine, eds. A Strange Freedom: The Best of Howard Thurman on Religious Experience and Public Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998.

- Smith, Jr., Luther E. Howard Thurman: Essential Writings. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2006.

References

[edit]- ^ Thurman, Howard (1998), "Introduction", in Fluker, Walter Earl; Tumber, Catherine (eds.), A Strange Freedom: The Best of Howard Thurman on Religious Experience and Public Life, Boston: Beacon Press, p. 2, ISBN 080701057X

- ^ "Howard Thurman Papers Project | Boston University". www.bu.edu. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fluker, Walter Earl; et al. (2009). The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Vol. 1: My People Need Me, June 1918-March 1936. Columbia: The University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-804-4.

- ^ "Howard University Libraries". Howard.edu. Archived from the original on March 31, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "Howard University School of Divinity". Divinity.howard.edu. Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Dixie, Quinton; Eisenstadt, Peter (2011). Visions of a Better World: Howard Thurman's Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Nonviolence. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 95–115. ISBN 978-0-8070-0045-8.

- ^ Dixie, Quinton; Eisenstadt, Peter (2011). Visions of a Better World: Howard Thurman's Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Nonviolence. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. xii. ISBN 978-0-8070-0045-8.

- ^ Sudarshan Kapur, Raising up a Prophet. The African-American encounter with Gandhi (Boston: Beacon Press 1992), pp. 81-93 (India trip), 87-90 (discussion with Gandhi), 89 (singing of Spiritual while Gandhi prayed), 88 & 89-90 (quotes).

- ^ "40 years after his death, iconic theologian still influences nonviolent protests". WFAE 90.7 - Charlotte's NPR News Source. November 26, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ "Howard Thurman receives his degree for Doctor of Divinity". www.digitalcommonwealth.org. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ Schachter-Shalomi, Reb Zalman; Gropman, Daniel (1983). The First Step: A Guide For the New Jewish Spirit. Toronto: Bantam. pp. 3–6. ISBN 9780553014181.

- ^ Austin, Charles (April 14, 1981). "Howard Thurman, Noted Black Cleric". The New York Times. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ Giles, Mark S. (2006). "Howard Thurman: The Making of a Morehouse Man, 1919-1923". Educational Foundations. 20: 115. ISSN 1047-8248.

- ^ Letter from Howard Thurman to Charles G. Proffitt, March 29, 1974 (Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, Boston Univ.)

- ^ "About Us". Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground. Boston University. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ^ "Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground". Boston University. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ "Welcome - Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center". hgar-srv3.bu.edu. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ "Howard Thurman Papers Project | Boston University". www.bu.edu. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ "Howard University School of Divinity". www.divinity.howard.edu. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Apel, William, "Mystic as Prophet: The Deep Freedom of Thomas Merton and Howard Thurman," in Merton Annual: Studies in Culture, Spirituality and Social Concerns, Vol. 16 (2003), 172–187.

- Dixie, Quinton and Eisenstadt, Peter. Visions of A Better World: Howard Thurman's Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Nonviolence. Boston: Beacon Press, 2011.

- Eisenstadt, Peter. Against the Hounds of Hell: A Life of Howard Thurman Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2021.

- Fluker, Walter Earl. "Dangerous Memories and Redemptive Possibilities: Reflections on the Life and Work of Howard Thurman," in Preston King and Walter Earl Fluker, eds., Black Leaders and Ideologies in the South: Resistance and Nonviolence. New York: Routledge, 2005, 147–176.

- Fluker, Walter Earl. "Leaders Who Have Shaped Religious Dialogue—Howard Thurman: Intercultural and Interreligious Leader," in Sharon Henderson Callahan, ed., Religious Leadership: A Reference Handbook (Vol. 2). Los Angeles: Sage, 2013, 571–578.

- Giles, Mark S. "Howard Thurman: The Making of a Morehouse Man, 1919–1923," The Journal of Educational Foundations 20:1–2 (2006), 105–122.

- Giles, Mark S. "Howard Thurman, Black Spirituality, and Critical Race Theory in Higher Education," Journal of Negro Education 79:3 (2010), 354–365.

- Haldeman, W. Scott. "Building a Reconciling Community: The Legacy of Howard Thurman," Liturgy 29:3 (2014), 31–36.

- Hardy III, Clarence E. "Imagine a World: Howard Thurman, Spiritual Perception, and American Calvinism," Journal of Religion 81:1 (2001), 78–97.

- Harvey, Paul. Howard Thurman and the Disinherited: A Religious Biography. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2020.

- Jensen, Kipton. "Howard Thurman: Philosophy, Civil Rights, and the Search for Common Ground," Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2019.

- Kaplan, Edward K. "A Jewish Dialogue with Howard Thurman: Mysticism, Compassion, and Community," CrossCurrents 60(4) (2010), 515–525.

- Neal, Anthony. Common Ground: A Comparison of the Ideas of Consciousness in the Writings of Howard Thurman and Huey Newton. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 2015.

- Neal, Anthony Sean. Howard Thurman’s Philosophical Mysticism: Love Against Fragmentation. New York: Lexington Press, 2019.

- Smith, Jr., Luther E. Howard Thurman: The Mystic as Prophet. Richmond, Ind.: Friends United Press, 1991 (first published in 1981).

- Walker, Corey D.B. "Love, Blackness, Imagination: Howard Thurman's Vision of Communitas," South Atlantic Quarterly 112:4 (2013), 641–655.

- Williams, Zachery. "Prophets of Black Progress: Benjamin E. Mays and Howard W. Thurman, Pioneering Black Religious Intellectuals," Journal of African American Men 5:4 (2001), 23–38.

External links

[edit]- The Howard Thurman and Sue Bailey Thurman Collections

- The Howard Thurman Papers Project

- "Howard Thurman", Chicken Bones: A Journal, a 1953 essay by Jean Burden reprinted from The Atlantic Monthly

- Howard Thurman, the first feature-length film about Howard Thurman

- "Howard Thurman", This Far by Faith, PBS

- Backs Against the Wall: The Howard Thurman Story. Description and link. A documentary film by Martin Doblmeier. Broadcast on PBS 2/18/2019.

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- Howard University faculty

- 1899 births

- 1981 deaths

- Morehouse College alumni

- People from Daytona Beach, Florida

- American Baptist theologians

- African-American history in San Francisco

- Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School alumni

- American nonviolence advocates

- Baptist philosophers

- Baptists from Florida

- Baptists from Virginia

- Baptists from Ohio

- Baptists from California

- 20th-century Baptists

- 20th-century African-American writers

- 20th-century Christian mystics