Red-billed quelea

| Red-billed quelea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male breeding plumage of Q. q. lathamii | |

| |

| Non-breeding plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Ploceidae |

| Genus: | Quelea |

| Species: | Q. quelea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Quelea quelea | |

| |

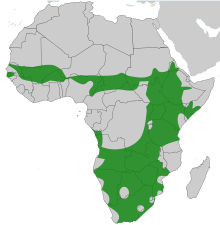

rough distribution[2]

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The red-billed quelea (/ˈkwiːliə/;[3] Quelea quelea), also known as the red-billed weaver or red-billed dioch, is a small—approximately 12 cm (4.7 in) long and weighing 15–26 g (0.53–0.92 oz)—migratory, sparrow-like bird of the weaver family, Ploceidae, native to Sub-Saharan Africa.

It was named by Linnaeus in 1758, who considered it a bunting, but Ludwig Reichenbach assigned it in 1850 to the new genus Quelea. Three subspecies are recognised, with Quelea quelea quelea occurring roughly from Senegal to Chad, Q. q. aethiopica from Sudan to Somalia and Tanzania, and Q. q. lathamii from Gabon to Mozambique and South Africa. Non-breeding birds have light underparts, striped brown upper parts, yellow-edged flight feathers and a reddish bill. Breeding females attain a yellowish bill. Breeding males have a black (or rarely white) facial mask, surrounded by a purplish, pinkish, rusty or yellowish wash on the head and breast. The species avoids forests, deserts and colder areas such as those at high altitude and in southern South Africa. It constructs oval roofed nests woven from strips of grass hanging from thorny branches, sugar cane or reeds. It breeds in very large colonies.

The quelea feeds primarily on seeds of annual grasses, but also causes extensive damage to cereal crops. Therefore, it is sometimes called "Africa's feathered locust".[4] The usual pest-control measures are spraying avicides or detonating fire-bombs in the enormous colonies during the night. Extensive control measures have been largely unsuccessful in limiting the quelea population. When food runs out, the species migrates to locations of recent rainfall and plentiful grass seed; hence it exploits its food source very efficiently. It is regarded as the most numerous undomesticated bird on earth, with the total post-breeding population sometimes peaking at an estimated 1.5 billion individuals. It feeds in huge flocks of millions of individuals, with birds that run out of food at the rear flying over the entire group to a fresh feeding zone at the front, creating an image of a rolling cloud. The conservation status of red-billed quelea is least concern according to the IUCN Red List.

Taxonomy and naming

[edit]The red-billed quelea was one of the many birds described originally by Linnaeus in the landmark 1758 10th edition of his Systema Naturae. Classifying it in the bunting genus Emberiza, he gave it the binomial name of Emberiza quelea.[5] He incorrectly mentioned that it originated in India, probably because ships from the East Indies picked up birds when visiting the African coast during their return voyage to Europe. It is likely that he had seen a draft of Ornithologia, sive Synopsis methodica sistens avium divisionem in ordines, sectiones, genera, species, ipsarumque varietates, a book written by Mathurin Jacques Brisson that was to be published in 1760, and which contained a black and white drawing of the species.

The erroneous type locality of India was corrected to Africa in the 12th edition of Systema Naturae of 1766, and Brisson was cited. Brisson mentions that the bird originates from Senegal, where it had been collected by Michel Adanson during his 1748-1752 expedition.[4] He called the bird Moineau à bec rouge du Senegal in French and Passer senegalensis erythrorynchos in Latin, both meaning "red-billed Senegalese sparrow".[6]

Also in 1766, George Edwards illustrated the species in colour, based on a live male specimen owned by a Mrs Clayton in Surrey. He called it the "Brazilian sparrow", despite being unsure whether it came from Brazil or Angola.[4] In 1850, Ludwig Reichenbach thought the species was not a true bunting, but rather a weaver, and created the genus name Quelea, as well as the new combination Q. quelea.[7] The white-faced morph was described as a separate species, Q. russii by Otto Finsch in 1877 and named after the aviculturist Karl Russ.[8]

Three subspecies are recognised. In the field, these are distinguished by differences in male breeding plumage.

- The nominate subspecies, Quelea quelea quelea, is native to west and central Africa, where it has been recorded from Mauritania, western and northern Senegal, Gambia, central Mali, Burkina Faso, southwestern and southern Niger, northern Nigeria, Cameroon, south-central Chad and northern Central African Republic.[9]

- Loxia lathamii was described by Andrew Smith in 1836,[10] but later assigned to Q. quelea as its subspecies lathamii. It ranges across central and southern Africa, where it has been recorded from southwestern Gabon, southern Congo, Angola (except the northeast and arid coastal southwest), southern Democratic Republic of Congo and the mouth of the Congo River, Zambia, Malawi and western Mozambique across to Namibia (except the coastal desert) and central, southern and eastern South Africa.[9][11]

- Ploceus aethiopicus was described by Carl Jakob Sundevall in 1850, but later assigned to Q. quelea as its subspecies aethiopica. It is found in eastern Africa where it occurs in southern Sudan, eastern South Sudan, Ethiopia and Eritrea south to the northeastern parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, Kenya, central and eastern Tanzania and northwestern and southern Somalia.[9][11]

Formerly, two other subspecies have been described. Q. quelea spoliator was described by Phillip Clancey in 1960 on the basis of more greyish nonbreeding plumage of populations of wetter habitats of northeastern South Africa, Eswatini and southern Mozambique. However, further analysis indicated no clear distinction in plumage between it and Q. quelea lathamii, with no evidence of genetic isolation.[12] Hence it is not recognised as distinct. Q. quelea intermedia, described by Anton Reichenow in 1886 from east Africa, is regarded a synonym of subspecies aethiopica.[13]

Etymology and vernacular names

[edit]Linnaeus himself did not explain the name quelea.[5] Quelea quelea is locally called kwelea domo-jekundu in Swahili, enzunge in Kwangali, chimokoto in Shona, inyonyane in Siswati, thaha in Sesotho and ndzheyana in the Tsonga language.[14] M.W. Jeffreys suggested that the term came from medieval Latin qualea, meaning "quail", linking the prodigious numbers of queleas to the hordes of quail that fed the Israelites during the Exodus from Egypt.[15]

The subspecies lathamii is probably named in honor of the ornithologist John Latham.[16] The name of the subspecies aethiopica refers to Ethiopia,[17] and its type was collected in the neighbouring Sennar province in today's Sudan.[18]

"Red-billed quelea" has been designated the official name by the International Ornithological Committee (IOC).[19] Other names in English include black-faced dioch, cardinal, common dioch, Latham's weaver-bird, pink-billed weaver, quelea finch, quelea weaver, red-billed dioch, red-billed weaver, Russ' weaver, South-African dioch, Sudan dioch and Uganda dioch.[4]

Phylogeny

[edit]Based on recent DNA analysis, the red-billed quelea is the sister group of a clade that contains both other remaining species of the genus Quelea, namely the cardinal quelea (Q. cardinalis) and the red-headed quelea (Q. erythrops). The genus belongs to the group of true weavers (subfamily Ploceinae), and is most closely related to the fodies (Foudia), a genus of six or seven species that occur on the islands of the western Indian Ocean. These two genera are in turn the sister clade to the Asian species of the genus Ploceus. The following tree represents current insight of the relationships between the species of Quelea, and their closest relatives.[20]

Interbreeding between red-billed and red-headed queleas has been observed in captivity.[7]

Description

[edit]The red-billed quelea is a small sparrow-like bird, approximately 12 cm (4.7 in) long and weighing 15–26 g (0.53–0.92 oz), with a heavy, cone-shaped bill, which is red (in females outside the breeding season and males) or orange to yellow (females during the breeding season).[7]

Over 75% of males have a black facial "mask", comprising a black forehead, cheeks, lores and higher parts of the throat. Occasionally males have a white mask.[8] The mask is surrounded by a variable band of yellow, rusty, pink or purple. White masks are sometimes bordered by black. This colouring may only reach the lower throat or extend along the belly, with the rest of the underparts light brown or whitish with some dark stripes. The upperparts have light and dark brown longitudinal stripes, particularly at midlength, and are paler on the rump. The tail and upper wing are dark brown. The flight feathers are edged greenish or yellow. The eye has a narrow naked red ring and a brown iris. The legs are orangey in colour. The bill is bright raspberry red. Outside the breeding season, the male lacks bright colours; it has a grey-brown head with dark streaks, whitish chin and throat, and a faint light stripe above the eyes. At this time, the bill becomes pink or dull red and the legs turn flesh-coloured.[7]

The females resemble the males in non-breeding plumage, but have a yellow or orangey bill and eye-ring during the breeding season. At other times, the female bill is pink or dull red.[7]

Newborns have white bills and are almost naked with some wisps of down on the top of the head and the shoulders. The eyes open during the fourth day, at the same time as the first feathers appear. Older nestlings have a horn-coloured bill with a hint of lavender, though it turns orange-purple before the post-juvenile moult. Young birds change feathers two to three months after hatching, after which the plumage resembles that of non-breeding adults, although the head is grey, the cheeks whitish, and wing coverts and flight feathers have buff margins. At an age of about five months they moult again and their plumage starts to look like that of breeding adults, with a pinkish-purple bill.[7]

Different subspecies are distinguished by different colour patterns of the male breeding plumage. In the typical subspecies, Q. quelea quelea, breeding males have a buff crown, nape and underparts and the black mask extends high up the forehead. In Q. quelea lathamii the mask also extends high up the forehead, but the underparts are mainly white. In Q. quelea aethiopica the mask does not extend far above the bill, and the underparts may have a pink wash. There is much variability within subspecies, and some birds cannot be ascribed to a subspecies based on outward appearance alone. Because of interbreeding, specimens intermediate between subspecies may occur where the ranges of the subspecies overlap,[7] such as at Lake Chad.[8]

The female pin-tailed whydah could be mistaken for the red-billed quelea in non-breeding plumage, since both are sparrow-like birds with conical red-coloured bills, but the whydah has a whitish brow between a black stripe through the eye and a black stripe above.[21]

Sound

[edit]Flying flocks make a distinct sound due to the many wing beats. After arriving at the roost or nest site, birds keep moving around and make a lot of noise for about half an hour before settling in.[7] Both males and females call.[22] The male sings in short bursts, starting with some chatter, followed by a warbling tweedle-toodle-tweedle.[2]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The red-billed quelea is mostly found in tropical and subtropical areas with a seasonal semi-arid climate, resulting in dry thornbush grassland, including the Sahel, and its distribution covers most of sub-Saharan Africa. It avoids forests, however, including miombo woodlands and rainforests such as those in central Africa, and is generally absent from western parts of South Africa and arid coastal regions of Namibia and Angola. It was introduced to the island of Réunion in 2000. Occasionally, it can be found as high as 3,000 m (9,800 ft) above sea-level, but mostly resides below 1,500 m (4,900 ft). It visits agricultural areas, where it feeds on cereal crops, although it is thought to prefer seeds of wild annual grasses. It needs to drink daily and can only be found within about 30 km (19 mi) distance of the nearest body of water. It is found in wet habitats, congregating at the shores of waterbodies, such as Lake Ngami, during flooding. It needs shrubs, reeds or trees to nest and roost.[7][2]

Red-billed queleas migrate seasonally over long distances in anticipation of the availability of their main natural food source, seeds of annual grasses. The presence of these grass seeds is the result of the beginning of rains weeks earlier, and the rainfall varies in a seasonal geographic pattern. The temporarily wet areas do not form a single zone that periodically moves back and forth across the entirety of Sub-Saharan Africa, but rather consist of five or six regions, within which the wet areas "move" or "jump". Red-billed quelea populations thus migrate between the temporarily wet areas within each of these five to six geographical regions. Each of the subspecies, as distinguished by different male breeding plumage, is confined to one or more of these geographical regions.[7]

In Nigeria, the nominate subspecies generally travels 300–600 km (190–370 mi) southwards during the start of the rains in the north during June and July, when the grass seed germinates, and is no longer eaten by the queleas. When they reach the Benoue River valley, for instance, the rainy season has already passed and the grass has produced new seeds. After about six weeks, the birds migrate northwards to find a suitable breeding area, nurture a generation, and then repeat this sequence moving further north. Some populations may also move northwards when the rains have started, to eat the remaining ungerminated seeds. In Senegal migration is probably between the southeast and the northwest.[7]

In eastern Africa, the subspecies aethiopica is thought to consist of two sub-populations. One moves from Central Tanzania to southern Somalia, to return to breed in Tanzania in February and March, followed by successive migrations to breed ever further north, the season's last usually occurring in central Kenya during May. The second group moves from northern and central Sudan and central Ethiopia in May and June, to breed in southern Sudan, South Sudan, southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya, moving back north from August to October.[7]

In southern Africa, the total population of the subspecies Q. quelea lathamii in October converges on the Zimbabwean Highveld. In November, part of the population migrates to the northwest to northwestern Angola, while the remainder migrates to the southeast to southern Mozambique and eastern South-Africa, but no proof has been found that these migration cohorts are genetically or morphologically divergent.[23]

Ecology and behaviour

[edit]The red-billed quelea is regarded as the most numerous undomesticated bird on earth, with the total post-breeding population sometimes peaking at an estimated 1.5 billion individuals.[7] The species is specialised on feeding on seeds of annual grass species, which may be ripe, or still green, but have not germinated yet. Since the availability of these seeds varies with time and space, occurring in particular weeks after the local off-set of rains, queleas migrate as a strategy to ensure year-round food availability. The consumption of a lot of food with a high energy content is needed for the queleas to gain enough fat to allow migration to new feeding areas.

When breeding, it selects areas such as lowveld with thorny or spiny vegetation—typically Acacia species—below 1,000 m (3,300 ft) elevation. While foraging for food, they may fly 50–65 km (31–40 mi) each day and return to the roosting or nesting site in the evening.[24] Small groups of red-billed queleas often mix with different weaver birds (Ploceus) and bishops (Euplectes), and in western Africa they may join the Sudan golden sparrow (Passer luteus) and various estrildids. Red-billed queleas may also roost together with weavers, estrildids and barn swallows.[7] Their life expectancy is two to three years in the wild, but one captive bird lived for eighteen years.[7]

Breeding

[edit]

The red-billed quelea needs 300–800 mm (12–31 in) of precipitation to breed, with nest building usually commencing four to nine weeks after the onset of the rains.[7][25]: 5, 12 Nests are usually built in stands of thorny trees such as umbrella thorn acacia (Vachellia tortilis), blackthorn (Senegalia mellifera) and sicklebush (Dichrostachys cinerea), but sometimes in sugar cane fields or reeds. Colonies can consist of millions of nests, in densities of 30,000 per ha (12,000 per acre). Over 6000 nests in a single tree have been counted.

At Malilangwe in Zimbabwe one colony was 20 km (12 mi) long and 1 km (0.6 mi) wide.[7] In southern Africa, suitable branches are stripped of leaves a few days in advance of the onset of nest construction.[26] The male starts the nest by creating a ring of grass by twining strips around both branches of a hanging forked twig, and from there bridging the gaps in the circle his beak can reach, having one foot on each of the branchlets, using the same footholds and the same orientation throughout the building process. Two parallel stems of reeds or sugar cane can also be used to attach the nest from. They use both their bills and feet in adding the initial knots needed.[27]

As soon as the ring is finished the male displays, trying to attract a female, after which the nest may be completed in two days. The nest chamber is created in front of the ring. The entrance may be constructed after the egg laying has started, while the male works from the outside.[25]: 6 [28][29] A finished nest looks like a small oval or globular ball of grass, around 18 cm (7 in) high and 16 cm (6 in) wide, with a 2.5 cm (1 in) wide entrance high up one side,[30] sheltered by a shallow awning. About six to seven hundred fresh, green grass strips are used for each nest.[4] This species may nest several times per year when conditions are favourable.[25]: 6

In the breeding season, males are diversely coloured. These differences in plumage do not signal condition, probably serving instead for the recognition of individual birds. However, the intensity of the red on the bills is regarded an indicator of the animal's quality and social dominance.[7] Red-billed quelea males mate with one female only within one breeding cycle.[25]: 7 There are usually three eggs in each clutch (though the full range is one to five) of approximately 18 mm (0.71 in) long and 13 mm (0.51 in) in diameter. The eggs are light bluish or greenish in colour, sometimes with some dark spots. Some clutches contain six eggs, but large clutches may be the result of other females dumping an egg in a stranger's nest.[7]

Both sexes share the incubation of the eggs during the day, but the female alone does so during the cool night, and feeds during the day when air temperatures are high enough to sustain the development of the embryo.[25]: 7 The breeding cycle of the red-billed quelea is one of the shortest known in any bird. Incubation takes nine or ten days.[4] After the chicks hatch, they are fed for some days with protein-rich insects. Later the nestlings mainly get seeds. The young birds fledge after about two weeks in the nest. They are sexually mature in one year.[7]

Feeding

[edit]Flocks of red-billed queleas usually feed on the ground, with birds in the rear constantly leap-frogging those in the front to exploit the next strip of fallen seeds. This behaviour creates the impression of a rolling cloud, and enables efficient exploitation of the available food. The birds also take seeds from the grass ears directly. They prefer grains of 1–2 mm (0.04–0.08 in) in size.[7] Red-billed queleas feed mainly on grass seeds, which includes a large number of annual species from the genera Echinochloa, Panicum, Setaria, Sorghum, Tetrapogon and Urochloa.[24]

One survey at Lake Chad showed that two-thirds of the seeds eaten belonged to only three species: African wild rice (Oryza barthii), Sorghum purpureosericeum and jungle rice (Echinochloa colona).[31] When the supply of these seeds runs out, seeds of cereals such as barley (Hordeum disticum), teff (Eragrostis tef), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), manna (Setaria italica), millet (Panicum miliaceum), rice (Oryza sativa), wheat (Triticum), oats (Avena aestiva), as well as buckwheat (Phagopyrum esculentum) and sunflower (Helianthus annuus) are eaten on a large scale. Red-billed queleas have also been observed feeding on crushed corn from cattle feedlots, but entire maize kernels are too big for them to swallow. A single bird may eat about 15 g (0.53 oz) in seeds each day.[24] As much as half of the diet of nestlings consists of insects, such as grasshoppers, ants, beetles, bugs, caterpillars, flies and termites, as well as snails and spiders.[7]

Insects are generally eaten during the breeding season, though winged termites are eaten at other times.[32] Breeding females consume snail-shell fragments and calcareous grit, presumably to enable egg-shell formation.[7] One colony in Namibia, of an estimated five million adults and five million chicks, was calculated to consume roughly 13 t (29,000 lb) of insects and 1,000 t (2,200,000 lb) of grass seeds during its breeding cycle.[24] At sunrise they form flocks that co-operate to find food. After a successful search, they settle to feed. In the heat of the day, they rest in the shade, preferably near water, and preen. Birds seem to prefer drinking at least twice a day. In the evening, they once again fly off in search of food.[25]: 11

Predators and parasites

[edit]

Natural enemies of the red-billed quelea include other birds, snakes, warthogs, squirrels, galagos, monkeys, mongooses, genets, civets, foxes, jackals, hyaenas, cats, lions and leopards. Bird species that prey on queleas include the lanner falcon, tawny eagle and marabou stork. The diederik cuckoo is a brood parasite that probably lays eggs in nests of queleas. Some predators, such as snakes, raid nests and eat eggs and chicks.

Nile crocodiles sometimes attack drinking queleas, and an individual in Ethiopia hit birds out of the vegetation on the bank into the water with its tail, subsequently eating them.[7] Queleas drinking at a waterhole were grabbed from below by African helmeted turtles in Etosha.[33] Among the invertebrates that kill and eat youngsters are the armoured bush cricket (Acanthoplus discoidalis) and the scorpion Cheloctonus jonesii.[34] Internal parasites found in queleas include Haemoproteus and Plasmodium.[7]

Interactions with humans

[edit]The red-billed quelea is caught and eaten in many parts of Africa. Around Lake Chad, three traditional methods are used to catch red-billed queleas. Trappers belonging to the Hadjerai tribe use triangular hand-held nets, which are both selective and efficient. Each team of six trappers caught about twenty thousand birds each night. An estimated five to ten million queleas are trapped near N'Djamena each year, representing a market value of approximately US$37,500–75,000. Between 13 June and 21 August 1994 alone, 1.2 million queleas were caught. Birds were taken from roosts in the trees during the moonless period each night. The feathers were plucked and the carcasses fried the following morning, dried in the sun, and transported to the city to be sold on the market.

The Sara people use standing fishing nets with a very fine mesh, while Masa and Musgum fishermen cast nets over groups of birds. The impact of hunting on the quelea population (about 200 million individuals in the Lake Chad Basin) is deemed insignificant.[35] Woven traps made from star grass (Cynodon nlemfuensis) are used to catch hundreds of these birds daily in the Kondoa District, Tanzania.[7]

Guano is collected from under large roosts in Nigeria and used as a fertiliser.[32] Tourists like to watch the large flocks of queleas, such as during visits of the Kruger National Park. The birds themselves eat pest insects such as migratory locusts, and the moth species Helicoverpa armigera and Spodoptera exempta.[7] The animal's large distribution and population resulted in a conservation status listed as least concern on the IUCN Red List.[1]

Aviculture

[edit]The red-billed quelea is sometimes kept and bred in captivity by hobbyists. It thrives if kept in large and high cages, with space to fly to minimise the risk of obesity. A sociable bird, the red-billed quelea tolerates mixed-species aviaries. Keeping many individuals mimics its natural occurrence in large flocks. This species withstands frosts, but requires shelter from rain and wind. Affixing hanging branches, such as hawthorn, in the cage facilitates nesting. Adults are typically given a diet of tropical seeds enriched with grass seeds, augmented by living insects such as mealworms, spiders, or boiled shredded egg during the breeding season. Fine stone grit and calcium sources, such as shell grit and cuttlebone, provide nutrients as well. If provided with material like fresh grass or coconut fibre they can be bred.[9]

Pest management

[edit]Sometimes called "Africa's feathered locust",[4] the red-billed quelea is considered a serious agricultural pest in Sub-Saharan Africa.[36]

The governments of Botswana, Ethiopia, Kenya, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe have regularly made attempts to lessen quelea populations. The most common method to kill members of problematic flocks was by spraying the organophosphate avicide fenthion from the air on breeding colonies and roosts. In Botswana and Zimbabwe, spraying was also executed from ground vehicles and manually. Kenya and South Africa regularly used fire-bombs.[37] Attempts during the 1950s and '60s to eradicate populations, at least regionally, failed. Consequently, management is at present directed at removing those congregations that are likely to attack vulnerable fields.[38] In eastern and southern Africa, the control of quelea is often coordinated by the Desert Locust Control Organization for Eastern Africa (DLCO-EA) and the International Red Locust Control Organization for Central and Southern Africa (IRLCO-CSA), which make their aircraft available for this purpose.[39]

Gallery

[edit]-

Etching by George Edwards published in 1760

-

male Q. q. aethiopica in breeding plumage with pink wash, Uganda

-

male Q. q. aethiopica in breeding plumage with a yellow wash on the head, Uganda

-

Females in breeding plumage with yellow bills, South Africa

-

female Q. q. aethiopica in non-breeding plumage, Ethiopia

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Quelea quelea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22719128A94613042. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22719128A94613042.en.

- ^ a b c Craig, Adrian J. F. (2020). "Red-billed quelea". Handbook of Birds of the World Alive. doi:10.2173/bow.rebque1.01. S2CID 216311213. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Quelea". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Red-billed Quelea". Weaver Watch. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis (in Latin). Vol. I (10th revised ed.). Holmiae: (Laurentii Salvii). p. 176 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1763). Ornithologia, sive, Synopsis methodica sistens avium divisionem in ordines, sectiones, genera, species, ipsarumque varietates : cum brevi & accurata cujusque speciei descriptione, citationibus auctorum de iis tractantium, nominibus eis ab ipsis impositis, nominibusque vulgaribus. Vol. 2. Lugduni Batavorum (Leiden, Netherlands): Apud Theodorum Haak. p. 337.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Cheke, Robert (2015). "Quelea quelea (weaver bird)". Invasive Species Compendium. University of Greenwich, United Kingdom. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Ward, Peter (1966). "Distribution, systematics, and polymorphism of the African weaver-bird Quelea quelea". Ibis. 108 (1): 34–40. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1966.tb07250.x.

- ^ a b c d "Zwartmasker roodbekwever Quelea quelea". Werkgroep voor Ploceidae (in Dutch). Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ Smith, Andrew (1836). "Report of the Expedition for Exploring Central Africa". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 6: 394–413. doi:10.2307/1797576. JSTOR 1797576.

- ^ a b Peters, James L. (1962). Check-list of the birds of the world. Volume 15. Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 62.

- ^ Jones, P.J.; Dallimer, M.; Cheke, R.A.; Mundy, P.J. (2002). "Are there two subspecies of Red-billed Quelea, Quelea quelea, in southern Africa?" (PDF). Ostrich. 73 (1&2): 36–42. Bibcode:2002Ostri..73...36J. doi:10.2989/00306520209485349. S2CID 84764540.

- ^ Reichenow, Anton (1900). Die Vögel Afrikas (in German). Vol. 3. Neudamm: J. Neumann. p. 109. ISBN 9785882381157.

- ^ "Roodbekwever Quelea quelea". Avibase. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 328. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Forshaw, Joseph M.; William T. Cooper (2002). Australian Parrots (3rd ed.). Robina: Alexander Editions. ISBN 978-0-9581212-0-0.

- ^ Orwa; et al. (2009). "Xylopia aethiopica" (PDF). Agroforestry Database 4.0. World Agroforestry Center. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ "NRM 568681 Ploceus aethiopicus Sundevall, 1850". Naturhistorica Riksmuseet.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2017). "Old World sparrows, snowfinches & weavers". World Bird List Version 7.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ De Silva, Thilina N.; Peterson, A. Townsend; Bates, John M.; Fernandoa, Sumudu W.; Girard, Matthew G. (2017). "Phylogenetic relationships of weaverbirds (Aves: Ploceidae): A first robust phylogeny based on mitochondrial and nuclear markers". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 109: 21–32. Bibcode:2017MolPE.109...21D. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.013. PMID 28012957. S2CID 205841906.

- ^ Weaver Research Unit. "Red-billed Quelea Quelea quelea". Weavers of the World. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Quelea quelea". Xeno-canto. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Dallimer, M.; Jones, P.J; Pemberton, J.M.; Cheke, R.A. (2003). "Lack of genetic and plumage differentiation in the red-billed quelea Quelea quelea across a migratory divide in southern Africa" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 12 (2): 345–353. Bibcode:2003MolEc..12..345D. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01733.x. PMID 12535086. S2CID 1191425.

- ^ a b c d Markula, Anna; Hannan-Jones, Martin; Csurhes, Steve (200). Red-billed quelea (PDF). Invasive animal risk assessment. Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, State of Queensland, Australia.

- ^ a b c d e f Abdelwahid, Amel Abdelraheem (2008). Monitoring and Habitat Location of the Weaver bird (Quelea quelea aethiopica) Using Remote Sensing And Geographic Information System (GIS) (PDF). University of Khartoum.

- ^ Johannes, Robert Earle (1989). Traditional Ecological Knowledge: A Collection of Essays. IUCN. ISBN 9782880329983.

- ^ Friedmann, Herbert (1924). "The weaving of the red-billed weaver bird, Quelea quelea in captivity". Zoologica. 2 (16): 357–372.

- ^ Crook, J. H. (1960). "Nest form and construction in certain West African weaver-birds". Ibis. 102: 1–25. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1960.tb05090.x.

- ^ Collias, Nicholas E.; Collias, Elsie C. (1962). "An Experimental Study of the Mechanisms of Nest Building in a Weaverbird" (PDF). The Auk. 79 (4): 568–595. doi:10.2307/4082640. JSTOR 4082640.

- ^ Goodfellow, Peter (2011). Avian Architecture: How Birds Design, Engineer, and Build. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 96. ISBN 9781400838318.

Red-billed quelea nest.

- ^ Crook, C.H.; Ward, P. (1967). "The Quelea Problem in Africa". In R.K. Murton; E.N. Wright (eds.). The Problems of Birds as Pests: Proceedings of a Symposium Held at the Royal Geographical Society, London, on 28 and 29 September 1967 (revised ed.). Elsevier.

- ^ a b Ward, Peter (1965). "Feeding ecology of the black-faced dioch Quelea quelea in Nigeria". Ibis. 107 (2): 173–214. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1965.tb07296.x.

- ^ Robel, Detlef (2008). "Turtles take Red-billed Quelea (Quelea quelea)" (PDF). Lanioturdus. 41.

- ^ Vincent, Leonard S.; Breitman, Ty (2010). "The scorpion Cheloctonus jonesii Pocock, 1892 (Scorpiones, Liochelidae) as a possible predator of the red-billed quelea, Quelea quelea (Linnaeus, 1758)" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Arachnological Society. 15 (2): 59–60.

- ^ Mulliè, Wim C. (2000). "Traditional capture of Red-billed Quelea Quelea quelea in the Lake Chad Basin and its possible role in reducing damage levels in cereals". Ostrich: Journal of African Ornithology. 71 (1–2): 15–20. Bibcode:2000Ostri..71...15M. doi:10.1080/00306525.2000.9639856. S2CID 84053588.

- ^ Shefte, N.; Bruggers, R. L.; Schafer Jr., E. W. (April 1982). "Repellency and Toxicity of Three Bird Control Chemicals to Four Species of African Grain-Eating Birds". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 46 (2): 453–457. doi:10.2307/3808656. JSTOR 3808656.

- ^ Elliott, Clive C.H. (2000). "5. Quelea Management in Southern and Eastern Africa" (PDF). In R.A. Cheke; L.J. Rosenberg; M.E. Kieser (eds.). Workshop on Research Priorities for Migrant Pests of Agriculture in Southern Africa, Plant Protection Research Institute, Pretoria, South Africa, 24 to 26 March 1999.

- ^ McCullough, Dale; Barrett, R.H. (2012). Wildlife 2001. Springer Sciencefiction & Business. ISBN 9789401128681.

- ^ "The Quelea Bird". Desert Locust Control Organization for Eastern Africa (DLCO-EA). Archived from the original on 28 May 2022.

External links

[edit] Data related to Quelea quelea at Wikispecies

Data related to Quelea quelea at Wikispecies- "Red-billed quelea media". Internet Bird Collection.