Mark of the Vampire

| Mark of the Vampire | |

|---|---|

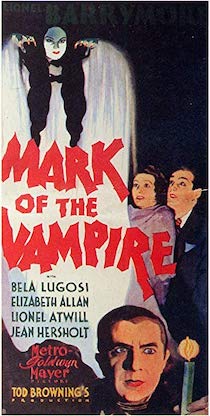

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tod Browning |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | James Wong Howe |

| Edited by | Ben Lewis |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 60 minutes (allegedly originally released in a longer cut)[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Mark of the Vampire is a 1935 American horror film directed by Tod Browning, and starring Lionel Barrymore, Elizabeth Allan, Bela Lugosi, Lionel Atwill, and Jean Hersholt, produced by Metro Goldwyn Mayer. Its plot follows a series of deaths and attacks by vampires that brings eminent expert Professor Zelen to the aid of Irena Borotyn, who is about to be married. Her father, Sir Karell, died from complete loss of blood, with bite wounds on his neck, and it appears he may be one of the undead now plaguing the area.

It has been described as a talkie remake of Browning's silent London After Midnight (1927), though it does not credit the older film or its writers.[1]

Plot

[edit]Sir Karell Borotyn is found murdered in his house, with two tiny pinpoint wounds on his neck. The attending doctor, Dr. Doskil, and Sir Karell's friend Baron Otto von Zinden are convinced that he was killed by a vampire. They suspect Count Mora and his daughter Luna, while the Prague Police Inspector Neumann refuses to believe them.

Sir Karell's daughter Irena is the Count's next target. Professor Zelen, an expert on vampires and the occult, arrives in order to prevent her death. After Irena is menaced by the vampires on several occasions, Zelen, Baron Otto, and Inspector Neumann descend into the ruined parts of the castle to hunt down the undead monsters and destroy them. When Zelen and Baron Otto find themselves alone, however, Zelen hypnotizes the Baron and asks him to relive the night of Sir Karell's murder. It is then revealed that the "vampires" are actually hired actors, and that the entire experience has been an elaborate charade concocted by Zelen in the hopes of tricking the real murderer —Baron Otto— into confessing to the crime. Acknowledging that the charade has failed to produce its intended results, Zelen, along with Irena and another actor who strongly resembles Sir Karell, compels the hypnotized Baron into re-enacting the murder, effectively proving his guilt. During the re-enactment, Baron Otto reveals his true motive: he wished to marry Irena, but her father would not allow it. He also reveals how he staged the murder to resemble a vampire attack.

With Baron Otto arrested, Irena explains the plot to her fiance, Fedor, who was not involved in the subterfuge and believed that the vampires were real. The film ends with the actors who played the vampires packing up their supplies, and "Count Mora" exclaiming, "This vampire business, it has given me a great idea for a new act! Luna, in the new act, I will be the vampire! Did you watch me? I gave all of me! I was greater than any real vampire!" His fellow thespians are not enthusiastic.

Cast

[edit]

- Lionel Barrymore as Professor Zelen

- Elizabeth Allan as Irena Borotyn

- Bela Lugosi as Count Mora

- Lionel Atwill as Inspector Neumann

- Jean Hersholt as Baron Otto von Zinden

- Henry Wadsworth as Fedor Vincente

- Donald Meek as Dr. J. Doskil

- Ivan F. Simpson as Jan

- Carroll Borland as Luna

- Leila Bennett as Maria

- June Gittelson as Annie

- Holmes Herbert as Sir Karell Borotyn

- Michael Visaroff as Innkeeper

- James Bradbury, Jr. as Third Vampire

- Egon Brecher as Coroner

- Jessie Ralph as Midwife (scenes deleted)

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The film's screenplay was co-written by Guy Endore, who had previously written the novels for The Werewolf of Paris (1933) and Babouk (1934).[3] The film had the working title Vampires of Prague.[4]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography began on January 12, 1935, and completed in mid-February 1935.[5] Co-star Carroll Borland had worked with Lugosi before, in a touring stage version of Dracula; she answered the casting call for the younger vampire role without being aware Lugosi was associated with the film, and won the part after the producers were impressed with how closely her physical movements resembled Lugosi's. She did not mention that they had previously worked together.[6][7] Makeup artist William J. Tuttle would later recollect to author Richard Bojarski,

The crew and I didn't like to work for director Tod Browning. We would try to escape being assigned to one of his productions because he would overwork us until we were ready to drop from exhaustion... he was ruthless. He was determined to get everything he could on film. If the crew didn't do something right, Browning would grumble: 'Mr. Chaney would have done it better.' He was hard to please. I remember he gave the special effects men a hard time because they weren't working the mechanical bats properly. Though he didn't drive his actors as hard, he gave Lionel Barrymore a difficult time during a scene. Lugosi's performance, however, satisfied Browning.[6]

— Richard Bojarski, The Films of Bela Lugosi (1980)

According to Borland, the ending of the film (which reveals the "vampires" to be actors hired to trick a murderer) was not revealed to the cast until the end of shooting; Browning felt that their performances would be negatively affected by knowing that they were not "real" vampires. She reports that an alternate ending – in which Professor Zelen receives a telegram from the hired actors revealing that they were unable to make their train (thus implying the vampires that the film depicts were real) – was considered but rejected by Browning.[1][8] She further claims that both she and Lugosi were disappointed with the ending, and found the twist "absurd."[8]

Release

[edit]Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released Mark of the Vampire theatrically on April 26, 1935.[5]

Alternate versions

[edit]

Early reviews of the film list running times of closer to 80 minutes, strongly suggesting that the film was cut back to 60 minutes by MGM after the early previews. This had led to much speculation about what the deleted footage contained.[1][2]

Several sources, including critic Mark Viera[9] and Turner Classic Movies writer Jeff Stafford,[6] have claimed that MGM cut out suggestions of incest between Count Mora (played by Lugosi) and his daughter Luna. Viera further claims that the original screenplay explained that Count Mora was condemned to eternity as a vampire for this crime and shot himself out of guilt (which explains the otherwise unaccountable spot of blood which appears on Lugosi's right temple during the film). This was an unacceptable topic according to the standards of the Production Code, and consequently cut from the film.[10] While the subplot was cut, the blood spot on Count Mora's face remains in the finished film and is never explained.[10]

Writer Gregory William Mank (who had access to the shooting script for his book Hollywood Cauldron) disputes these claims, asserting that the original cut was only 75 minutes (the reports of an 80+ minute run time being the result of a misprint) and that most of the cuts were either exposition or comedy. He further asserts that the alleged incest subplot was never in the shooting script and never filmed, though he acknowledges that it was likely hinted at in the original scenario for the film written by Guy Endore. This claim is backed up by Borland, who points out that the studio would never have allowed such content to be filmed.[11]

Lugosi biographer Arthur Lennig asserts that Endore did originally intend an incest backstory, but that it was removed by the studio before the shooting script was written, though he goes on to claim that a cut line of dialogue indicates that Count Mora shot himself after strangling his daughter.[12]

In the commentary which accompanies the film on the Hollywood Legends of Horror boxed set released by Warner Home Video, genre historians Kim Newman and Steve Jones seem to concur with Mank, hypothesizing that primarily comedic material—possibly related to the maid character played by Leila Bennett—was cut.[13]

Home media

[edit]MGM/UA Home Video released Mark of the Vampire on VHS in October 1987.[14] The Warner Archive Collection released the film on Blu-ray on October 11, 2022.[15]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Mark of the Vampire was a moderate box-office success, earning Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer a profit of $54,000[16] (equivalent to $1,200,058 in 2023).

Critical response

[edit]Upon its initial release, reviews of the film were relatively positive; a New York Times review by Frank Nugent claimed the film would "catch the beholder's attention and hold it, through chills and thrills ..." The review finished, "Like most good ghost stories, it's a lot of fun, even though you don't believe a word of it."[17] It received similar praise from The Los Angeles Times, The Hollywood Reporter, and Motion Picture Daily.[18] The film did draw some distinct criticism as well, most notably from Dr. William J. Robinson, who claimed in a letter to the New York Times that,

... a dozen of the worst obscene pictures cannot equal the damage that is done by such films as The Mark of the Vampire [sic]. I do not refer to the senselessness of the picture. I do not even refer to the effect in spreading and fostering the most obnoxious superstitions. I refer to the terrible effect that it has on the mental and nervous systems of not only unstable, but even normal men, women and children. I am not speaking in the abstract; I am basing myself on facts. Several people have come to my notice who, after seeing that horrible picture, suffered nervous shock, were attacked with insomnia, and those who did fall asleep were tortured by the most horrible nightmares. In my opinion, it is a crime to produce and to present such films. We must guard not only our people's morals -- we must be as careful with their physical and mental health.[16]

— William J. Robinson, Letter to the New York Times, 28 July 1935

Seymour Roman of the Brooklyn Times-Union praised the film as "a gloriously unrestrained example of the cinema [of the] supernatural, thrilling, chilling, and horrifying."[19]

Modern evaluations of the film are more mixed, largely due to the ending, which reveals that the vampires were actors hired to help trap a murderer (the twist is very similar to Browning's previous London After Midnight, where Lon Chaney's vampire character is ultimately revealed to be a detective in disguise). While it was not unusual for 1920s films such as The Cat and the Canary or The Gorilla to end with a revelation that the supernatural threat was a fraud, 1930s films such as Dracula and The Mummy presented the supernatural elements as real, making Mark of the Vampire something of an anachronism for its time (particularly since Browning and Lugosi were most known for Dracula just a few years earlier).[20] Some viewers thought that the ending compromised the film;[6] Bela Lugosi reportedly found the idea absurd.[8] Some critics, including genre critics Kim Newman and Steve Jones, have suggested the film may be a satire of the conventions of the horror film, pointing to the broad performances by Barrymore and some of the supporting characters, as well as the film's twist ending.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Mark of the Vampire". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "Mark of the Vampire (1935)". Turner Classic Movies. TCM Film Notes. Archived from the original on August 6, 2024.

- ^ "'Mark of the Vampire' Thrilling, Chilling, and Shocking Murder Mystery". Havre Daily News. May 18, 1935. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wood, Bret (October 26, 2006). "Insider Info (Mark Of The Vampire) - Behind the Scenes". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "Mark of the Vampire (1935) – Original Print Info". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Stafford, Jeff (September 27, 2002). "Mark of the Vampire". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020.

There is also that surprise ending which some horror fans feel negates the supernatural qualities of the film.

- ^ Lennig 2010, p. 219.

- ^ a b c Lennig 2010, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Viera 2003, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Viera 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Mank 1994, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Lennig 2010, p. 220.

- ^ a b Kim Newman and Steve Jones (2006). Commentary: Mark of The Vampire (DVD Commentary). Warner Brothers.

- ^ "'Mark of Vampire' still satisfying; casting helps 'Rock, Pretty Baby!'". Sun Sentinel. October 30, 1987. p. 45 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mark of the Vampire (1935) - Warner Archive Collection". High-Def Digest. Archived from the original on January 22, 2025.

- ^ a b Mank 2009, p. 226.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (May 3, 1935). "MOVIE REVIEW: At the Rialto and the Mayfair". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2025.

- ^ Wood, Bret. "TCMDb Archive Materials - Mark of the Vampire". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on August 6, 2024.

- ^ Roman, Seymour (May 25, 1935). "'Mark of the Vampire'". Brooklyn Times-Union. p. 5A – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Worland 2006, p. 56.

Sources

[edit]- Lennig, Arthur (2010). The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-813-12661-6.

- Mank, Gregory William (1994). Hollywood Cauldron: 13 Horror Films from the Genres's Golden Age. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-41112-2.

- Mank, Gregory William (2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: The Expanded Story of a Haunting Collaboration, with a Complete Filmography of Their Films Together. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-43480-0.

- Viera, Mark A. (2003). Hollywood Horror: From Gothic To Cosmic. New York City, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0-810-94535-7.

Worland, Rick (2006). The Horror Film: An Introduction (First ed.). Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-13902-1.

External links

[edit]- 1935 films

- 1935 horror films

- American detective films

- American supernatural horror films

- American vampire films

- American black-and-white films

- Films directed by Tod Browning

- Films set in Prague

- Gothic horror films

- Horror film remakes

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Remakes of American films

- Sound film remakes of silent films

- 1930s American films

- 1930s supernatural horror films