Idu script

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (September 2020) |

| Idu script | |

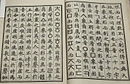

A page from the 19th-century yuseopilji. | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 이두 |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Idu |

| McCune–Reischauer | Idu |

|

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

|

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

| Transliteration |

|

Idu (Korean: 이두; Hanja: 吏讀; lit. 'official's reading') is an archaic writing system that represents the Korean language using Chinese characters ("hanja"). The script, which was developed by Buddhist monks, made it possible to record Korean words through their equivalent meaning or sound in Chinese.[1]

The term idu may refer to various systems of representing Korean phonology through hanja, which were used from the early Three Kingdoms to Joseon periods. In this sense, it includes hyangchal,[2] the local writing system used to write vernacular poetry[2] and gugyeol writing. Its narrow sense only refers to idu proper[3] or the system developed in the Goryeo (918–1392), and first referred to by name in the Jewang ungi.

Background

[edit]The idu script was developed to record Korean expressions using Chinese graphs borrowed in their Chinese meaning but it was read as the corresponding Korean sounds or by means of Chinese graphs borrowed in their Chinese sounds.[4] This is also known as Hanja and was used along with special symbols to indicate indigenous Korean morphemes,[5] verb endings and other grammatical markers that were different in Korean from Chinese. This made both the meaning and pronunciation difficult to parse, and was one reason the system was gradually abandoned, to be replaced with hangul, after its invention in the 15th century. In this respect, it faced problems analogous to those that confronted early efforts to represent the Japanese language with kanji, due to grammatical differences between these languages and Chinese. In Japan, the early use of Chinese characters for Japanese grammar was in man'yōgana, which was replaced by kana, the Japanese syllabic script.

Characters were selected for idu based on their Korean sound, their adapted Korean sound, or their meaning, and some were given a completely new sound and meaning. At the same time, 150 new Korean characters were invented, mainly for names of people and places. Idu system was used mainly by members of the Jungin class.

One of the primary purposes of the script was the clarification of Chinese government documents that were written in Chinese so that they can be understood by the Korean readers.[6] Idu was also used to teach Koreans the Chinese language.[6] The Ming legal code was translated in its entirety into Korean using idu in 1395.[7] The same script was also used to translate the Essentials of agriculture and sericulture (Nongsan jiyao) after it was ordered by the King Taejong in 1414.[7]

Example

[edit]The following example is from the 1415 book Yangjam Gyeongheom Chwaryo (양잠경험촬요; 養蠶經驗撮要, lit. 'Collected Summary of the Experiences of Silkworm Cultivation').

| Literary Chinese | 蠶陽物大惡水故食而不飮 |

|---|---|

| Idu transcription | 蠶段陽物是乎等用良水氣乙厭却桑葉叱分喫破爲遣飮水不冬 |

| Old Korean | 蠶ᄯᆞᆫ 陽物이온ᄃᆞ로ᄡᅥ 水氣ᄅᆞᆯ 厭却 桑葉ᄲᅮᆫ 喫破ᄒᆞ고 飮水안ᄃᆞᆯ |

| Modern Korean | 누에는 양물로써, 물기를 싫어해, 뽕잎만 먹고, 물을 마시지 않는다. |

| Meaning | Silkworm is Yang (positive) animal, it doesn't like moisture, so it eats mulberry leaves but not drinks water. |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lowe, Roy & Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2016). The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge Networks and the Early Development of Universities. Oxon: Taylor & Francis. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-138-84482-7.

- ^ a b Grimshaw-Aagaard, Mark; Walther-Hansen, Mads & Knakkergaard, Martin (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-19-046016-7.

- ^ Li, Yu (2019-11-04). The Chinese Writing System in Asia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-00-069906-7.

- ^ Sohn, Ho-Min & Lee, Peter H. (2003). "Language, forms, prosody and themes". In Lee, Peter H. (ed.). A History of Korean Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780521828581.

- ^ Hannas, William C. (2013-03-26). The Writing on the Wall: How Asian Orthography Curbs Creativity. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0216-8.

- ^ a b Allan, Keith (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 222. ISBN 9780199585847.

- ^ a b Kornicki, Peter Francis (2018). Languages, scripts, and Chinese texts in East Asia. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780198797821.

- Lee, Peter H., ed. (2003). A History of Korean Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521828581.

- Nam Pung-hyeon (남풍현) (2000), Idu Study [吏讀研究], Seoul, Korea: Taehak Publishing (太學社)